Compusearch (now Unison) was a visionary company with visionary goals. But, as often happens with visionary companies, focus on a long-term strategy to revolutionize a market can mean that near-term execution and operationalization can suffer, creating barriers to growth.

In Compusearch’s case, the company had set out to transform how federal government agencies procure and contract for goods and services.

From its founding in 1983, the company used state-of-the-art software design and development to provide solutions that streamlined and automated key steps in government procurement, purchasing, and contract management.

In 2005, the company arrived at a strategic decision point. The company’s team of owner-operators decided to sell the company and retire. The new owner, private equity firm The Carlyle Group (Carlyle), saw immense potential in the company and its pedigree of quality innovation.

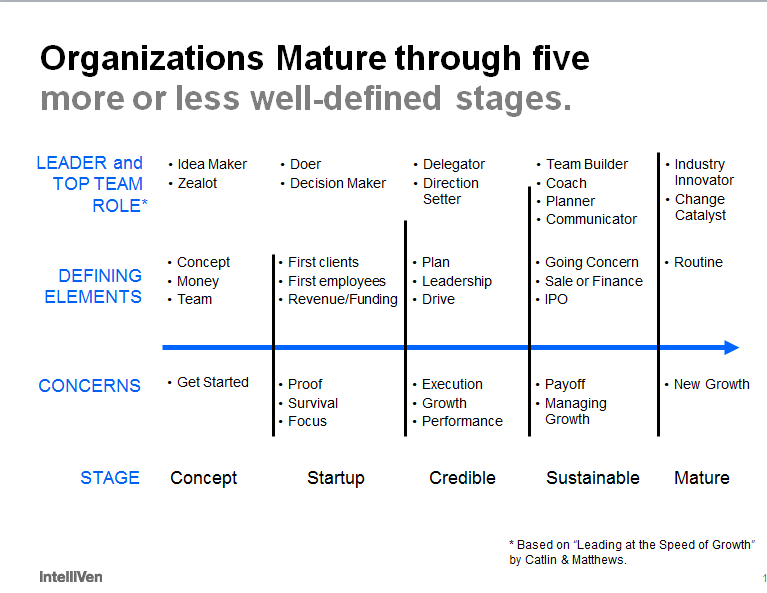

But Carlyle also saw that the change in ownership was an ideal time to assess how the organization operated and to upgrade to more effective strategy execution and operations maturity. Maturing operations turned out to be essential to achieving the goal to double revenue and increasing margins to realize a 4X return on invested capital within five years.

Highly innovative companies often suffer from a lack of focus on operating fundamentals, which becomes an impediment to growing to the next stage of maturity. Carlyle saw evidence that Compusearch could benefit from a renewed and refreshed approach to turning its vision into action.

Carlyle and Compusearch engaged IntelliVen to assess the company’s operational maturity, develop a plan to implement strategy, and generate more effective performance to drive growth.

The Challenges

Like many visionary companies, Compusearch had become a decisive market leader with a strategy of continuous innovation and breaking new ground with its solution offerings.

By 2005, the company had reached $15 million per year in revenue. Its procurement and purchasing solutions were operating in nine cabinet-level departments and related agencies across the United States federal government.

It had achieved this leadership position by continually updating and innovating its solutions as software design and the underlying system capabilities evolved over two decades.

The company’s newest solution was web-based software to support government contract officers who procure, contract, and requisition the spending, granting, and moving of public funds in compliance with mandated government rules, transparency, efficiency, and control.

IntelliVen guided the company’s top team through its structured process to get aligned, on track, and then grow. Alignment came from the clarity reached by the team jointly making explicit what they each saw, and what they were each thinking, so they could then work together to come up with a consolidated view of where things were and what they needed to do.

1. Great vision but not enough focus on operational execution

Compusearch had reached a leadership position in its industry by pursuing a vision with continuous innovation. But oftentimes this approach can cause a company to become distracted. It ends up chasing the new technology and functionality without tuning its operations and processes to generate the most value from the innovations it has already brought to market. There were many more opportunities for the company to extend and expand the value it provided to current customers with its existing solutions at existing customers.

2. Lack of coordinated direction and team alignment

The executive team in Compusearch was made up of highly experienced managers who knew the market and their functional domains of responsibility. But there was no consistent melding of vision and strategy coordinated across functional teams, to ensure everyone was always rowing in the same direction. As a result, the company found itself often in reaction mode, not effectively promoting its current offerings to customers to generate more business. Key items fell between organizational units, resulting in unmet client needs, as well as confounded employees. In some cases, initiatives were confined to a particular unit, such as the development team, without the full benefit of coordination with other groups such as those providing customer services.

3. No clear process for strategy operationalization

Like many companies, the corporate vision for revolutionizing federal government contracting was well understood by top executives. But exactly how that vision translated into individual goals, commitments, and resource allocation was not all that clear. Each executive had to decide for themselves how best to support overall corporate goals.

4. Inconsistent and ineffective use of metrics for tracking and accountability

Compusearch executives collected and studied metrics that were relevant to their own functional domains. But they were not as effective at combining and assessing these metrics in terms of the story they told for overall corporate performance and strategy implementation. A sales leader would announce a customer win that generated widespread acclaim in the company. But it was rare for anyone to ask whether the price was aligned with the firm’s strategy or if the licensing terms would generate the most value over the long term.

The Solutions: Aligning Compusearch for Execution

IntelliVen Founder and Managing Partner, Peter DiGiammarino, worked with the new Compusearch CEO, Reid Jackson, to explore how a new, fresh approach to strategy execution and operating practices could be implemented across the company.

Together they implemented four initiatives using IntelliVen tools, workstreams, and tutorials for best practice operations.

1. Effective focus on strategy implementation: the W-W-W and Initiative-to-Action

Peter introduced the W-W-W model – the exercise in which senior managers gain great clarity on

- WHAT they are selling.

- WHO is buying it.

- WHY they buy it.

By working together to reach a common, crisp and simple understanding of the overarching purpose of the company in this way, the company core leadership team instantly become more closely aligned in terms of strategy and action. As Peter describes it, nailing down the W-W-W is the first step any organization needs to take to enable a team to, “Get clear, Align, and Grow!”

Peter also provided the team with guidance to turn strategy into reality using the IntelliVen Initiative-to-Action template.

The Initiative-to-Action template helps ensure that strategic planning session outcomes are acted upon. It requires managers to connect the dots between corporate strategy, the case for change, individual goals, resource allocation, performance metrics, actions, timetable, accountability, and outcomes.

2. Core leadership team alignment: set direction, execution focus, incentives

The new model for the executive team featured cross-team communication and cross-organizational performance tracking. That way, each executive knew what was required of her/his group and, in turn, could clearly identify the needs they had for others. The resulting cross-team dependency tracking set the direction for the team and focused the executives on execution. The new accountability was enhanced by tying executive incentives to hitting cross-group targets in addition to individual performance goals to align resources.

3. Strategy operationalization: market expansion, sales execution, accountability & governance

Clarity on strategy and aligning the team in the same direction allowed the Compusearch team to then explore executing more effectively on the overall strategy.

For example, the team saw new opportunities for revenue expansion in existing customers with solution refinements, such as offering new billable services that previously had been a support expense.

Knowing who to count on for what made it possible to also introduce new responsibilities such as account and project management. Every employee could see clearly what s/he could do to step up to and help identify, develop, and deliver on every opportunity to provide more value to customers.

Lastly, the new approach to operationalization created a framework for accountability and governance. Now each executive and each member of the staff understood what was expected of them and performance against these requirements was easy to measure and track.

4. Metrics to drive and track effective operationalization

With the newfound accountability and alignment of goals and dependencies, the executive team had the ability to use key metrics to track and improve execution and operationalization.

The performance of every department – product engineering, customer support, professional services, marketing, sales – could be tracked and evaluated using metrics and benchmarks that guided team decisions and next actions.

When these metrics indicated a problem was arising in a given area, the team could readily see how each member could contribute to address the problem. The approach promoted accountability for execution and brought leadership together as a high-performance team that worked to make each other – and the company as a whole –successful.

The Outcomes: Compusearch’s organization evolution and growth

With the IntelliVen best practices guidance, Compusearch embarked on a transformation that resulted in much more effective execution and strategy operationalization.

The results were dramatic increases in top-line revenue, growing more than 200 percent in four years. Other impacts included:

- Driving the EBITDA-margin plus growth-rate to over 50.

- Increasing recurring revenue to more than half of total revenue.

- Shifting from selling one product in a narrow market to selling multiple products into multiple markets while at the same time maximizing revenue from existing customers.

Compusearch had achieved a much more advanced stage of organization maturity. After four years of growth, the company sold for a ~4X multiple of invested capital. The company was eventually renamed Unison and, over the past ten years has successfully executed its business and financial plans, completed a handful of accretive acquisitions with more on the horizon, and is on track to exceed $150 million in annual revenue. All-and-all a great win-win-win-win-win: for the company, its customers, employees, investors, and the community in which it operates.

Postscript

Fifteen years from the beginning of the case, the company was acquired for the fourth time … again by The Carlyle Group, the very same team that acquired it the first time!